PZN: You say potato, I say civil war...

Click photo to play

Length: 6:29

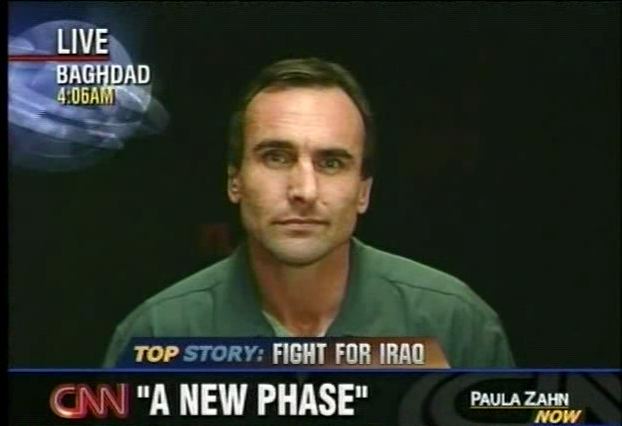

JOHN ROBERTS: Let's move on to Baghdad. Tonight, the Bush administration is acknowledging that the violence in Iraq has entered a new phase, as they say. But National Security Adviser Stephen Hadley won't use the words civil war.

CNN's Michael Ware joins us now from Baghdad.

And, Michael, is it really just a game of semantics here? The White House won't use the word civil war. Some American news organizations, including "The Los Angeles Times," are beginning to use it.

Does it really make any difference as to what it is on the ground?

MICHAEL WARE, CNN CORRESPONDENT: Well, I don't think anyone here really cares what it is called. They know what it is. They have to live it day in, day out.

And, to them, it is civil war. You talk to al Qaeda commanders, they think they're in civil war. You talk to the Mahdi army commanders, they think they're in civil war.

You talk to the families that are too scared to leave their homes, that can't send their kids to school, for fear of crossing sectarian lines, where teachers probably won't show up anyway, whose neighborhoods have fighting positions dug in, who, each night, the father has to join with others to fend off death squads in police uniforms, institutionalized hit teams, where you have parliament restricting access to the media, because what is being said could be considered to be inflammatory, you have got Sunni patients being pulled out of Shia-run hospitals and never seen again; to them, this is civil war.

And, by any academic's definition, this is civil war, organized conflict by two elements within a country to pursue the political center, with elements of ethnic cleansing, militia combat, family against family, neighbor against neighbor, with a degree of organization and coordination.

John, you can tick all of those boxes. So, whether the White House calls it civil war or not, the fact on the ground is, if this isn't civil war, we don't want to see one when it comes.

ROBERTS: Michael, Nouri al-Maliki, the prime minister, said that the politicians have the power within them to stop this violence. Is there any suggestion that the politicians have any interest in squelching the violence at this point?

WARE: Well, it is really not up to the politicians, per se.

I mean, let's look at this government of Nouri al-Maliki to begin with. To what degree does it really exist, behind his prime ministerial office and the office of the national security adviser? Beyond that, this administration is merely an amalgam, or an alignment, of various Shia and Kurdish militias.

Now, for the Shia militias, there's absolutely no interest whatsoever in relenting right now. And al Qaeda and the Sunni extremists are gaining more and more foot soldiers as a result of these front lines being created along the sectarian divide. So, no. Who is going to listen to these people?

ROBERTS: Some people have suggested that this is a countrywide version of what Chicago was like in the 1930s. It's almost gangland there.

Jamie McIntyre, 3,700 Iraqis died last month, according to the United Nations. Is that a suggestion that, despite their best efforts to get between these two sides, that the fighting is so intense, that the American military really is powerless to stop these killings?

MCINTYRE: Well, you know, I guess there's a level of military force that you could apply, you know, equivalent to sort of martial law, that could restore order.

But, you know, the real problem is here, is, there really isn't much debate among experts that this really is a civil war. To the extent people want to argue whether it is a low-level civil war, a full-blown civil war, it could be even a worse civil war, that's -- that's true.

The problem is that, once you label this a civil war, then, you have to admit that the strategy that the United States and the Iraqi government is employing is not the right strategy to end a civil war. So, they insist on not calling it a civil war.

ROBERTS: Yes. They keep calling it a counterinsurgency.

But, Michael Ware, as long as these two sides continue to go at each other, they're going to be causing pain and suffering for normal Iraqis. Is there still a sense -- you mentioned family-on-family violence there, neighbor against neighbor. But is there still a sense that the majority of ordinary Iraqis just want to live their lives in peace; they want to see this all go away?

WARE: Without a shadow of a doubt.

The ordinary Iraqi civilian just wants to return to some essence of normal life, to have a job, and to be able to drive to it and come home at night safely, to be able to send the kids to school, and know that they will come home, for the shopper in the family to be able to go to the market without having fear of it being wrenched apart, to sleep in your bed at night without fear of men in government uniforms with government I.D. bursting in the door, dragging you away from your family, and having them never see you again. That's what they want.

ROBERTS: And what I got from some families who wouldn't be the target of these reprisal killings, but are still worried, they say, the thing that they worry most about are the mortars, the mortars that get flung into their neighborhoods on a nightly basis.

Jamie McIntyre, if the Iraq Study Group comes out with its recommendations in the next week or two, how long could it take for those to filter through the system, until they finally get implemented on the ground in Iraq?

MCINTYRE: Well, you know, it really depends on whether they come out with a major change in strategy or whether they tinker with the strategy that is in place now.

And, of course, one of the problem is, if you radically change the strategy -- for instance, if you put all the emphasis on coming up with some sort of a power-sharing or peace agreement, and then try to enforce that, as opposed to continuing to build up the Iraqi army, one side against the other, the problem is, if it is too big a change, you're really sort of repudiating the military judgment of some of the generals who are in charge, who have basically said: We think we're following the right strategy.

So, in a way, because there's civilian control of the military, what you would really have to do is maybe fire or replace some of the top generals with somebody who agrees with the new strategy, because, right now, you have got General Abizaid, General Casey arguing that, basically, what they're doing now is the right thing.

So, it is hard to see how you have a major change, and then you just ram that down the throat of the commanders, who, at this point, are saying they don't think it's the right thing to do.

ROBERTS: Going to be interesting to find out if this is actually going to have an impact or it will be one of those studies that just ends up on the shelf.

Jamie McIntyre, Michael Ware, thanks very much. Appreciate it.