Iraq: Inside the Surge

Part 1 -- Length: 8:42

LARGE (102.0 MB) ----- SMALL (10.5 MB)

Michael's second special for CNN/International explains the surge and how the different aspects of it have lowered the levels of violence, and the costs (both military and social) of how we achieved them.

ANNOUNCER: It appears to be America's best hope for changing its fortunes in Iraq: combating insurgent violence with a temporary flexing of military muscle. So far, the results are encouraging. Now, as the US Ambassador to Iraq and the top US General there prepare to give a new assessment of this strategy, we bring you a look at what it means to Iraqis and to the troops charged with making it work.

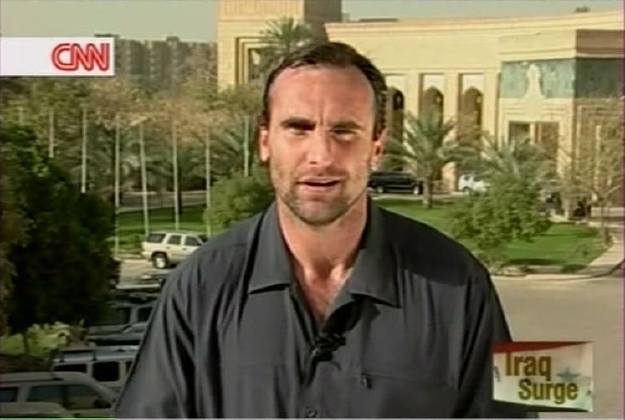

This is a CNN Special Report: Iraq: Inside the Surge. From the Iraqi capital, here's Michael Ware.

MICHAEL WARE: Hello. Welcome to Baghdad, and the American military's "surge." A lot of people talk about the surge -- perhaps America's most effective strategy in the Iraq war -- but few talk about what it really is.

The true nature of the surge and what's driving its successes goes far beyond the 30,000 combat troops sent here to reinforce the capital.

We talk to US Special Forces and field commanders, insurgent leaders, US allies, and both the Iranian and American Ambassadors.

But to begin, we look at exactly what is the surge.

(voiceover) This is the face of America's surge. Abu Fahad, leader of a US-backed militia. Last year we couldn't reveal his identity. But now we can… he's dead, murdered one month after walking me through these alleys, targeted for allying with America.

His was a true frontline of the surge. It was his own neighborhood. Defending it against al-Qaeda and Shia death squads, he did it all under contract with US forces.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Somebody's there just watching. He'll pop out again.

WARE: When President Bush unveiled his surge strategy in January last year, ordering 30,000 extra troops to Baghdad, he vowed their mission would prevail.

GEORGE W. BUSH, PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES: This time we will have the force levels we need to hold the areas that have been cleared.

WARE: But the surge is much more than force levels. It's a shift in strategic thinking, comprising many components.

First, helping Sunni militia to target al-Qaeda, cutting deals with insurgents who'd been fighting Americans, putting over 70,000 of them on Washington's payroll, some of whom treat al-Qaeda without mercy.

"These are the men who hold the areas now cleared," this senior insurgent commander tells me. "It's the agreement that made the violence against the Americans go down," he says. "And if the Americans say it was because of troop numbers, that will provoke the resistance."

Even Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, an opponent of the U.S. presence, plays a part in the surge, reining in his Mehdi Army militia with a cease-fire; a cease-fire that's held, despite a government offensive on his Mehdi Army strongholds in Basra.

Then, off the battlefield, there's the political surge: an American push for Iraq's government to pass key legislation that's had mixed results.

Much more visible: the lines of blast walls built by the Americans. They encircle neighborhoods, walling off Sunni communities from Shia. Their exits guarded with checkpoints, they've turned Baghdad into a segregated city, even changing how Iraqis get married. For this groom, a Sunni marrying a Shia, collecting his bride from her neighborhood, controlled by the Mehdi Army, could be a death sentence.

"I was forced to decorate two cars for the wedding," he says. "One for driving in my neighborhood. And another for traveling through hers."

But the surge remains an undeniable success. Though spiking in recent weeks, attacks nationwide are down 60 percent on last year, with violence at levels not seen since 2005, according to the U.S. military, with sectarian killings plunging by as much as 95 percent. These successes would evaporate without U.S. troops. But the troops haven't done it alone.

"We had to start this," Abu Fahad said, "but we're putting death in front of our eyes. We're being put under a lot of pressure to stop. But we won't."

Yet it wasn't long before he was stopped, making his death forever part of America's surge.

They were told to expect the worst. Ordered into a Baghdad stronghold of the Mehdi Army, the militia loyal to Muqtada al-Sadr, Bravo Company of the 1-502 Air Assault Regiment went ready for battle. But what they found surprised them all: a quiet neighborhood. Where units before them waged torrid battles, Bravo Company patrols in simple 8-man teams, roaming out from a small outpost nestled within the neighborhood of Shu'ala -- a fresh military approach, coupled with American political accommodation for Muqtada and his militia following the cleric's ceasefire declaration.

Flowing from that accommodation, these paratroopers partner with Iraqi Army units drawn from the Shu'ala neighborhood itself; the Iraqi recruits most likely drawn from the Mehdi militia.

CAPTAIN JEREMY USSERY, BRAVO COMPANY COMMANDER: I'm willing to work with anybody that's got a nationalistic approach. You know, where their loyalties lie, we always have to keep that in the back of our heads and not be foolish about it, but at the same time, we have to have a semi-optimistic and realistic approach towards training these guys.

WARE: An optimism that doesn't blind the captain to the threat he says he faces: Iranian-backed "Special Groups." Well-trained, well-armed guerrilla teams modeled on the Shia militia in Lebanon: Hezbollah.

And on the eve of the war's fifth anniversary, that threat's made real. Humvees rolling out of Captain Ussery's post after a rocket-propelled grenade attack on US soldiers nearby. They return with a wounded soldier, rushed onto a medivac chopper, the outpost's second evacuation in twelve hours. The previous night, one of Captain Ussery's own men was hurt on a patrol targeting rebel gunmen. The young paratrooper stretchered by his comrades, he'd been thrown from the top of an armored vehicle by an electrical wire strung across the street.

But those scenes are increasing rare for Bravo Company, their days spent foot-patrolling more than fighting. Or endlessly readying weapons and keeping vigil. Or carving a new post out of empty warehouses. Their lives are basic -- makeshift showers, side mirrors for shaving, and food trucked in and eaten in a Spartan chow hall -- with violence still present: days after this patrol, a carbomb in the neighborhood killed five civilians.

USSERY: Just about every day you find a IED or EFP or something, and nobody every knew anything.

WARE: Nothing here is ever easy. And when the surge ends, its legacy will fall upon units like Bravo Company, and their war will continue.

1ST SERGEANT RICK SKIDIS, BRAVO COMPANY: It's just another day, man. And we'll go out and do our best and try to get everybody home.

Part 2 -- Length: 11:18

LARGE (132.4 MB) ----- SMALL (13.5 MB)

WARE: According to a United Nations count, 633 Iraqi civilians were killed in February this year. A drop from the 1807 killed in the same month last year. The greatest factor behind this relative relief in the bloodshed is America's agreement with its insurgent enemies, which so far is a huge success. But could the deal have been struck years ago? And could thousands of Iraqi and American lives have been saved?

(voiceover) When horror is commonplace, an old man barely flinches as a Humvee erupts in a blast behind him. An attack videoed by an insurgent faction still at war with America even as other factions from the same group, the Islamic Army of Iraq, have allied with America, joining 70,000 guerillas now on the US government payroll.

Announcing the surge a year ago, the US administration warned there would be trade-offs -- this deal with enemies it once called "terrorists" was the greatest trade-off of all. From American commanders to the US president, it's acknowledged that rather than fighting Sunni insurgents, enlisting them in the so-called "Awakening" program has dampened the violence. Yet the deal was a long time coming.

From the beginning, the insurgents were willing to negotiate. Talks with American officials began way back in 2004. But why did so much American and Iraqi blood have to be spent before agreement was found?

COLONEL RICK WELCH, US ARMY SPECIAL FORCES: I think we didn't recognize all the opportunities when they presented themselves because we saw all of these groups through one lens and didn't really have the mechanism in place to talk about specific strategies with each group.

WARE: Green Beret Colonel Rick Welch is one of the original architects of the covert discussions with insurgent leaders that opened four years ago.

WELCH: We saw everyone through the lens of anti-Iraqi forces, but it was quite a complex time. We did not distinguish national resistance groups from al-Qaeda or insurgents or terrorists. But that was a distinction those groups had, and it was an important distinction for some of those groups.

WARE: Abu Ahmed, a top commander of the Mujahideen army, now running a US-backed militia, remembers the frustration. "The delay pointed to the Americans' fears," he told me. "The delay to distinguish the national resistance from al-Qaeda was understandable though painful."

Years later, it took a seismic shift in American thinking for the deal to finally work.

WELCH: General Petraeus and his vision on counterinsurgency began to drive that through the organization. You have to change course a little bit. Ambassador Crocker -- I mean, getting some people coming at the right place at the right time.

WARE: Key to the breakthrough was America dropping its insistence on including the Iraqi government in the arrangement. Now, the Sunni militias are a check against the Iranian-influenced regime in Baghdad.

MAJOR GENERAL KEVIN BERGNER, MULTINATIONAL FORCE, IRAQ: So it's a period of time where there has to be some confidence-building measures, there has to be some trust developed, because in some cases these are folks who were once fighting this government.

WARE: Folks with intentions to fight again, should the Americans leave Iraq. Despite the risks, it's the opportunities and lives lost that give most pause.

WELCH: Well, I guess in the pure sense of it, yes. I mean, if we had-- if we could have seen everything as clearly then as we see it now, maybe we could have avoided-- our policies would have reflected our clarity of vision.

WARE: A clarity Colonel Welch and others had from the beginning, but which took time for America's leaders to share.

(on camera) One of the men key to the success of the surge is US Ambassador Ryan Crocker. Career diplomat, fluent in Arabic, he is America's point-man in Iraq.

The first American ambassador to meet face-to-face with an Iranian counterpart in almost three decades, I sat down with Ambassador Crocker to discuss the state of Iraq, and the future of the American mission.

Mr. Ambassador, the surge has been an unquestioned success in reducing violence. But the term has taken on a life of its own. How do you define the surge?

RYAN CROCKER, US AMBASSADOR TO IRAQ: It's a great question, because for me it is more than simply the increase in the number of troops, as obviously vital as that has been. It is the surge on the civilian side, it's the Iraqi surge. We surged by approximately 30,000 troops; the Iraqis in the course of 2007 put over 100,000 additional men in uniform, Army and police, into this fight.

And finally, if you will -- and this may be the most important element of it all -- it's the political and the economic surge, which I think by definition is a follow-on action. The transformation in Sunni attitudes that we saw in the course of 2007 -- first in Anbar, then in Baghdad and the areas around Baghdad -- had a huge impact, not only in the fight against al-Qaeda but in the overall security climate. And that was followed by Sayid Muqtada al-Sadr's announcement of a freezing of militia activities that was then renewed in February.

WARE: Hasn't this program required a significant shift in American strategic thinking, to distinguish nationalist insurgents from al-Qaeda insurgents?

CROCKER: You cannot kill your way out of an insurgency. You've got to make distinctions between reconcilables and irreconcilables with the aim of reducing the latter group to the smallest possible number. That means among the reconcilables, clearly we're going to be dealing with people who stood against us in the past and have our blood on their hands.

WARE: And it's going to require great patience from the American people.

CROCKER: It will require great patience. That's what I referred to earlier when I spoke of the need for strategic patience here. Things are moving in the right direction. I think that is a sustainable process, if we keep at it. And clearly there are costs. There have been enormous costs in both human and financial terms, and people ask themselves, is it worth it?

My answer is, yes it is. The gains are substantial but they're reversible. If we were to decide we're done here, then I think you would see things spiral very, very quickly.

WARE: It could get bad?

CROCKER: It could get very bad.

WARE: In what way?

CROCKER: Well, if we decide we're going to disengage for reasons of our own -- in other words, reasons not based on conditions on the ground in Iraq -- then I think you see a reversal of this whole process. I think you'd see the process stop at every level -- neighborhood, local, provincial, and national -- as the different communities look to their own survival and basically re-supplied and re-armed.

And then I think the fight would be on, and on at a level that we just haven't seen here before.

WARE: Are we talking about regional proxy war?

CROCKER: Well, I think that's the possibility you have to look at, because as bad as it was in 2006 -- and no-one knows better than you how bad it was -- we were here. If we spiral into conflict again and we're leaving, everybody knows we're not coming back. So I think the gloves then come completely off, and it's in that environment that the risk of regional involvement in the conflict, particularly from Iran, becomes very grave indeed.

WARE: Is Iran the big winner of the last five or six years, or not?

CROCKER: Iran could be in a very good position. I say could be because I think they've made some pretty poor strategic choices of their own.

WARE: But surely it played to their strategic advantage, the removal of Saddam, the vacuum that followed, their well-positioned ability to manipulate that situation?

CROCKER: Well, that's why I said could be. The overthrow of Saddam Hussein to their west, the overthrow of the Taliban to their east, removed their two greatest enemies in the region. That should give them a very strong incentive to support the new order in both Afghanistan and in Iraq.

WARE: Well then, just within your purview, what exactly is your strategy for curbing and combating growing Iranian influence here in Iraq? Indeed, the White House, when the surge was announced, talked about removing Iranian actors who have infiltrated into Iraqi institutions. What exactly is your strategy for combating this influence?

CROCKER: Well, in terms of Iranian actors such as Quds Force officers, any of them that come into Iraq and we find them, we're going to detain them.

WARE: Some of your own intelligence agencies would name some of the most senior officials in this country as Iranian agents of influence, with interventions in the arrests of Quds Force officers in the past and more recently. Isn't this a concern for you?

CROCKER: Well, clearly Iran has been a negative influence in Iraq, as we've just been discussing, but they do not have unchecked opportunity here. Iran, as we know, is Persian, it is not Arab. Iraq's Arab identity is intensely felt by all of its Arab population, Shia as well as Sunnis. And Iraqi Shias died by the hundreds of thousands in the Iran/Iraq war, defending their Arab homeland of Iraq. That isn't forgotten. There is a lot of bitterness, indeed, on both sides. So there is a limit, I think, to Iranian influence for historical and cultural reasons.

Part 3 --Length: 4:50

LARGE (56.7 MB) ----- SMALL (5.8 MB)

WARE: When Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad visited Baghdad recently, unlike American dignitaries, he announced his arrival weeks in advance and eschewed the security of the US-built Green Zone -- a display of Tehran's confidence in its influence in Iraq… influence that rivals America's.

(voiceover) Streets of conflict and the chatter of gunfire. And perhaps a foretaste of an Iraq after American withdrawal. Opposing Shia factions -- some in uniform, others not; all linked to Iran -- vying violently for power in the southern city of Basra. A massive Iraqi government military offensive blunted by militia resilience. The offensive has unmasked the Army's deficiencies and exposed limits to Washington's influence while highlighting the ascendancy of Tehran's. As American forces advised overwhelmed Iraqi officers, Iran seized the moment to host Iraqi delegations on Iranian soil, brokering the deal that took the guns off Basra's streets.

It was a display of the influence Iran wields across much of Iraq; influence America seeks to contain, but Iran's ties are well-entrenched. The building blocks of Iraq's government are political groups linked to Iran through funding, military support, or long association. One of the government's most dominant factions was actually created in Tehran; it's paramilitary wing served in the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps. And American debate calling for their soldiers to come home aligns with Iranian policy, which long advocated American withdrawal.

HASSAN KAZEMI QOMI, IRANIAN AMBASSADOR TO IRAQ (translated): If Americans want a break from their problems here and problems which have overshadowed their domestic life, then they have to give responsibility for security to the Iraqi government and give it full sovereignty over its own matters and allow regional countries to cooperate with the new Iraq.

WARE (voiceover): Cooperation in which Iran assumes the role the US plays now.

QOMI (translated): Undoubtedly, countries in the region, including Iran, can help the government of Iraq to build a professional defense and security structure through training and transfer of experience.

WARE: The US condemns the covert campaign by Iran's elite Quds Force units, directing Shia militia to attack US forces in Iraq.

BERGNER: Well, we have said for quite some time that we know that there are elements of extremist groups here in Iraq who are dependant upon both Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps' Quds Force for material support as well as funding, as well as training, and they have -- the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps' Quds Force -- has also used Lebanese Hezbollah as a proxy of sorts, a surrogate, to execute their policy here in Iraq.

WARE (voiceover): Claims Iran's ambassador brushes away.

QOMI (translated): Unfortunately, Iran and the US interactions have been hostile, and in the past, since the victory of the Islamic revolution, these hostilities and allegations but have had no affect on the Islamic Iran's will and its constructive role in Iraq.

WARE: US commanders say that will is to use the Iraq battlefield to weaken US resolve on a range of issues, like Iran's nuclear program. They say the supply of Iranian-made roadside bombs known as EFPs to Iraqi militia fits into that strategy.

USSERY: Lost a soldier due to an EFP, so-- that was actually in establishing our JSS [Joint Security Station], so they're-- like I said, they're lethal.

WARE: Is that hard to take?

USSERY: Well, you ever lost a brother? That's what it's like.

WARE: As the flow of those bombs into Iraq continues and factional fighting like this in Basra still threatens, the true dynamic of the Iraq war increasingly becomes America's confrontation with Iran.

(on camera) Though the surge is coming to an end, America's presence in Iraq is not. As US commander General David Petraeus so often reminds, the situation is too tenuous. So the questions now are: what form will the US presence take, and what kind of Iraq will emerge?

From Baghdad, I'm Michael Ware. Thank you for joining us.