NR: "Essentially, they're an insurance policy."

June 28, 2009

Length: 5:29

LARGE (63.6 MB) ----- SMALL (6.7 MB)

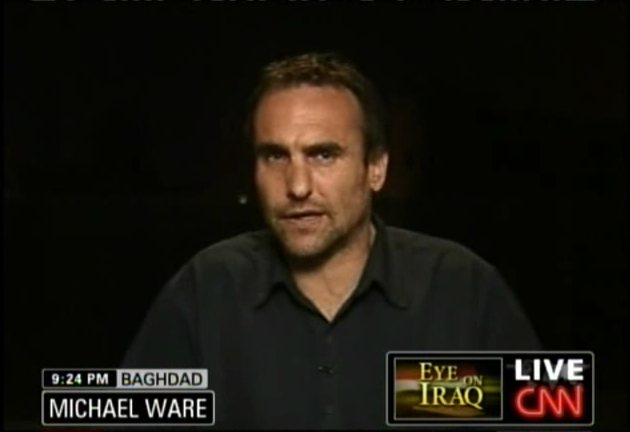

Michael's prepared piece on the handover, followed by a Q&A with Fredricka Whitfield about the new role for US troops still in Iraq.

FREDRICKA WHITFIELD: All right, Tuesday's the deadline for most American troops to withdraw from Iraqi cities. the move, pushed by the Iraqi government, comes at a time of stepped-up violence in Baghdad and other cities. CNN's Michael Ware is in Baghdad.

MICHAEL WARE (voice-over): After so much of this -- American troops in blazing combat -- the American-led war in Iraq is coming to an end. Despite successful elections and the people's return to a vaguely normal life, this is how the US withdrawal is beginning to look: a bombing in a Baghdad market where 72 people out shopping were killed. Or here, this mosque in the north, where a suicide truckbomber killed 80. Or in this Baghdad market for used motorbikes, with 15 more slain. In less than a week, more than 200 Iraqis have been butchered across the country, prompting the government to warn people to stay away from crowded locations.

For one thing is almost certain: these attacks will continue, as al Qaeda and its allies attempt to bomb Iraq back into sectarian civil war. A war it will be up to Iraq's prime minister to prevent, for this no longer will be America's war. By June 30, all US forces will have retreated to their bases outside of Iraq cities and towns. After six long, brutal years, they're now reduced to a supporting role at the behest of the Iraqis.

Though 130,000 troops will remain, they'll be unable to launch operations of their own within the cities, nor even detain suspected enemy combatants without the permission or invitation of the government of Iraq. That leaves some Iraqis fearful, like Hannah Abdul Hassan, who says the handover fills her with horror. "My message to the US military and their commander as they're going to move away from us," she says, "is that we want you to still keep your eye on us."

But most Iraqis are glad to see the Americans out of their neighborhoods. State TV is fonted with a countdown marking time to the handover, and June 30 has been declared a national holiday.

"I feel the same as most Iraqis feel," says [name unclear]. "I will feel my freedom and my liberation when I don't see an American stopping an Iraqi on the street just 20 or 30 meters ahead of me."

The soldier's departure from those streets, though a few soldiers will remain to advise the Iraqis of work and occasional joint operations, is dictated by an agreement signed in the dying days of the Bush administration, an agreement that surrenders the United States' ability to wage the war it began.

And as much as Iraqi emotions will be mixed, June 30 will be a day bittersweet for Americans. Though the first step in bringing their troops home, something the agreement gives them only 18 more months to do, it's an event that intones the memory of the American blood that's been spilt. Already, some US officials are aggrieved by the notion of an Iraqi national holiday, feeling such celebration belies the 4,300 troops who have died on Iraqi soil. Those deaths a bloody legacy the US will leave forever in Iraq, but it's a legacy that will be measured against the kind of Iraq America will eventually leave behind.

WHITFIELD: And Michael Ware now joins us live from Baghdad. So, Michael, you talk about there are expressed mixed-concerns among Iraqis but what about among US troops? You did mention mixed emotions but how much are they conveying to you?

WARE: Well, obviously it's a very difficult time for everybody here, Fredricka, and the US troops -- I mean, this is a time of enormous change. I mean, 130.000 American combat troops are still here but their role now is very, very different. That's a big transition. They can't go out and hunt for the bad guys, so to speak, as they used to, and as fighting men and women--

WHITFIELD: It sounds more like a humanitarian mission now, right?

WARE: Well, no, not exactly, because they're not really delivering aid, they're not bringing sacks of wheat and flour. They're not so much into the school-building business as they once were. The hearts-and-minds campaign has now taken a different tack and we're seeing the return of groups like UNICEF and the UN has been re-imprinting its stamp here after it was chased out of Iraq by a massive bombing against it back in 2003. What they're here for, according to their commanders, is stability operations. Essentially, they're an insurance policy -- Fredricka.

WHITFIELD: All right. Thanks so much, Michael Ware, then, from Baghdad. Appreciate that, and of course we look forward to your continuing reporting as we now approach that Tuesday withdrawal.