Newsweek: The Things War Makes You See

Michael Ware on the Things War Makes You See

May 28, 2012 1:00 AM EDT

I should be dead. I wish I was.

Those eight words were not easy to write. It’s even harder now reading them back. Seeing them there, sullen and sad and monosyllabic in their black and white.

For the longest time I wished I was dead. I wished one of my multitude of near-misses wasn’t. Later there then came a time—when I’d first stopped living in war and first found Brooklyn—a time when I consciously, achingly desired death. Craved it. Longed so hard and bitterly for it that it became some taut tripwire strung within me where no one could see. But then, perhaps, thinking back, decoding it anew, maybe the wish was not to be dead? Not entirely? Not when I drill down into it. Maybe my wish rather was for all the pain to simply end?

Yes, that’s starting to seem more like it. Maybe it wasn’t death I wanted so much as it was oblivion.

I won’t tell you how close I did or did not come in those angry days, after what feels now like an unspeakable decade of reporting wars; wars from Lebanon to Georgia, to Pakistan and Afghanistan; all mere accompaniments to six or seven years in Iraq. But I will tell you of when, on a day I cannot distinctly remember, that I came to know I wouldn’t do it. That no matter what, no matter how badly I pined for it, I would nonetheless continue. Even if that meant being sentenced to a slow, quiet torment for the term of my natural life. That was the day I finally accepted it was a choice no longer mine to make.

I know one day my now-young son will read this, hopefully when he himself is a man. I pray not sooner. It’s for him, and only for him, that I resisted. Once I realized even a deadbeat father, should I become one, is still better than the specter of a dead dad, especially at his own hand.

The decision, however, was far from palliative. I’ve since had thoughts, remembrances of that urge, despite knowing the execution of them is off the table. Because it doesn’t alter the immutable sense that my race is run. That I’m done. That all the rest, now, is busy work.

To this day my mind still reels with war’s usual kaleidoscope: dead kids splayed out, often in bits; screaming mates; crimson tides from al Qaeda suicide bombings creeping across asphalt. I still see ... things.

Other things I cannot remember, even when told of them, but I know they haunt my sleep; I tore my left shoulder right out of its socket during a dream one Friday night; awakened by the hellish sound of someone screaming before realizing it was me. So, yes, I still see things.

Mired in a falsehood of self-medication, I applied blizzards of booze and drugs to buy me time. To get me from one dawn to another sleep. To give me the time to reconcile my decision to live. All stealing for me just one more day, one more day. Though in a perverted way it helped save me, it didn’t immunize me against the price for it all.

For now, I’m deprived of the right to see the boy I’m still here for, though he lives but blocks away and drives twice daily to school past my apartment.

I feel chewed and spat out by my past employers. In the field it was only a colleague—a mate and true brother in arms, with me everywhere—who helped me at all. And then, in New York, two other friends, both cameramen, discreetly found the doctor I went on to see in secret for almost two years. His bills came out of my pocket, no recompense from those who paid me for my wars. From them came only rebuke and lectures. Somehow I was in a blind spot of sorts in their mirror of what was going on. After, when I’d quit, my health care evaporated, my insurance checks halted. I don’t blame my superiors for their blundering, though the sense welling within me that I’d been gravely wronged persists.

But all that’s OK. I’m adapting, surviving, and, in time, I’ll overcome. Just as we all have to out There. There, where our friends die. Where I won the lottery by making it through, though I’ll never forgive myself for my fortune.

A soldier’s lot once back is often with The Damned. For some it’s part of the service offered as young men, and so it has always been. Return passage. Homecoming. All too often they’re brittle deceits woven from straw so easily blown away by no more than the coming home itself. By war’s nature it’s an alien horror understood only by the few. Nothing will change that. Ever. Rendering a year’s tour, commonly more, deposits of service and good will in faraway accounts forever frozen, the contents never to be truly repatriated.

But so it goes. We just have to suck it up. As we did the blood and sweat and sand. As we did on patrol, or over watch. As we did on cordons-and-knocks, on sweeps, in hides, in gun pits, in turrets, and on chopper doors. As we did killing or capturing or merely waving to children through Humvee windows.

Because of all of those things and more, our peace times are not necessarily so. But I wish it less now than I did. To be dead, that is. Time’s passage let me discover that the desire diminishes, that it mellows even as it rages, and that, possibly, it eventually quiets. I know it’s been my silent brooding companion; familiar, intimate. But I told the doctors. I even confided in my parents, now elderly, and they have watched their son grow older than them right before their eyes.

I’m here to tell you none of us has any choice. Because living is there to be done and it’s we who must do it. It must become our new mission. Because when our generation was called it was we who answered. And our Fallen cannot be left behind. It is we who must remember them.

So, if but one of you reads this, sees this, stumbles over it and you give me just one more day as a result, then this humiliation will have been worth it. Please allow me just to say to you, with no particular expectation at all:

DON’T.

--------------------

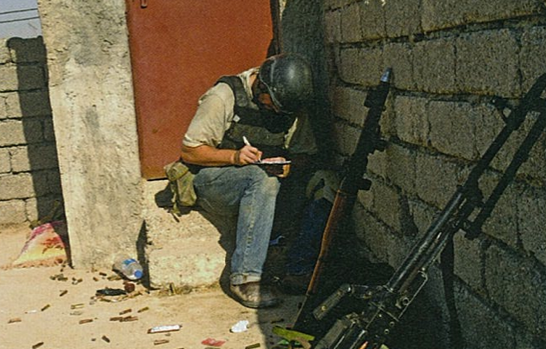

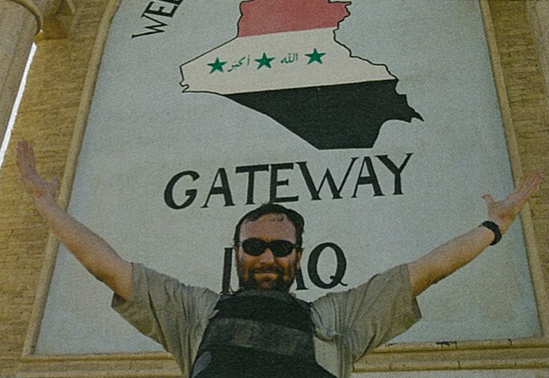

(these photos ran in the print edition only)

all photos by Franco Pagetti / VII

The Things War Makes You See (link to The Daily Beast)

**********

When Michael told me that he had written a column about suicide -- about wanting to commit suicide -- it was immediately obvious that it was going to be gut-wrenching to read. It's hard to imagine how difficult it must be to write honestly and openly about such intense pain, to bare your soul to the world.

We live in a judgmental society and many will choose to judge Michael because of what he has revealed -- most will do so with no clue of the torment and darkness he is living with; some few may even do so having lived through it themselves with no lasting ill effects.

Fortunately for all of us, he is a man who doesn't care how others judge him. He cares only about being honest. This is what he experienced, this is how he feels, this is what makes him want to avoid sleep and the dreams he cannot block.

In the years I have known Michael, even during the darkest days in Baghdad and New York, I never feared he would commit suicide for one reason: his son. When he wrote to me about his little boy, especially when he was back home on breaks, his attitude changed, his mood lifted. Some may say that he should not have returned to covering the wars once he had a child, but just as so many soldiers cannot easily make the transition back to ’normal’ life, neither could he; perhaps that is difficult for most of us to understand but the commitment to the work and the weight of responsibility to those still fighting is real. Yet I can vouch for the fact that he loves his son fiercely.

My fear these past years has been more of the accidental overdose of prescribed or self-medicated drugs… the Heath Ledger danger. It can happen to anyone, and the more sleep-deprived you are, the more easily it can occur. But there really is no way to guard against it, other than getting to the point that you are less dependent on drugs and are once again able to sleep -- that's an issue between him and his doctors which no amount of worrying can prevent.

But I spoke to him at some length shortly after he submitted this column and I can say this: Michael can now see a glimmer of light at the end of the proverbial tunnel. I don't think he even realized it WAS a tunnel, thought he'd just always be lost in the dark. He is working his way through this and it is a hard, painful slog. As he does, he is producing what I believe will be some incredibly evocative work that gives the rest of us a window into war and the hell that so many of our young men and women experienced in the past decade. Not a sanitized G-rated three-minute sip but full-body emersion into the sights and sounds of battle.

No amount of honesty can make us fully understand. But we owe it to our soldiers -- and our friends -- to try.